Police investigate heart deaths at NHS hospital

BBC

BBCPolice have launched an investigation into the deaths of patients following heart operations at an NHS hospital, the BBC has learned.

Documents seen by us suggest patients suffered avoidable harm – and that in some cases their death certificates failed to disclose that the procedure contributed to their deaths.

One woman’s operation at Castle Hill Hospital near Hull – that should have taken no more than two hours – has been described as a “disaster” by one medic.

She spent six hours in surgery and lost five litres of blood – all while under local anesthetic.

But none of this was mentioned on her death certificate, which recorded her as dying from pneumonia. Her family were also not told what had happened.

The NHS body that runs Castle Hill, the Humber Health Care Partnership, told the BBC it had delivered improvements suggested by the Royal College of Physicians (RCP). In a statement, it said it was happy to directly answer any questions from the patients’ families.

Humberside Police said an investigation was “in the very early stages” and no arrests had been made.

‘Very concerned about safety’

The documents raise concerns about the care that 11 patients received during a TAVI – Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implant – a procedure to replace a damaged valve in the heart, similar to adding a stent.

The department’s TAVI mortality rate at the time was three times higher than the UK average, something patients and families were also unaware of.

Staff concerns within the hospital led managers to commission several reviews – but none was made public. In 2020, the RCP was asked to assess the whole cardiology department, in which the TAVI team was operating, including two of the TAVI deaths.

That report, completed in 2021, led to a second review conducted by consultants IQ4U, which recommended a third review of all 11 deaths, which was also conducted by the Royal College and completed in early 2024.

The BBC has been passed copies of all three inquiries. The patients’ families only found out they had taken place when we contacted them.

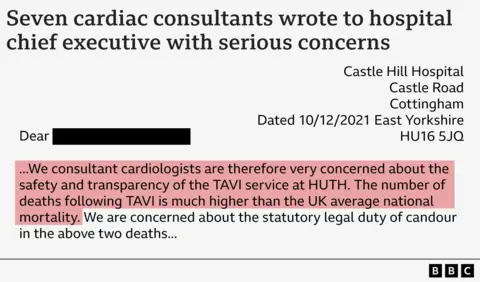

Also in 2021, seven cardiac consultants wrote they were “very concerned about the safety and transparency of the TAVI service” in a letter to the hospital’s chief executive. It followed the deaths, in less than six months, of four of the 11 patients.

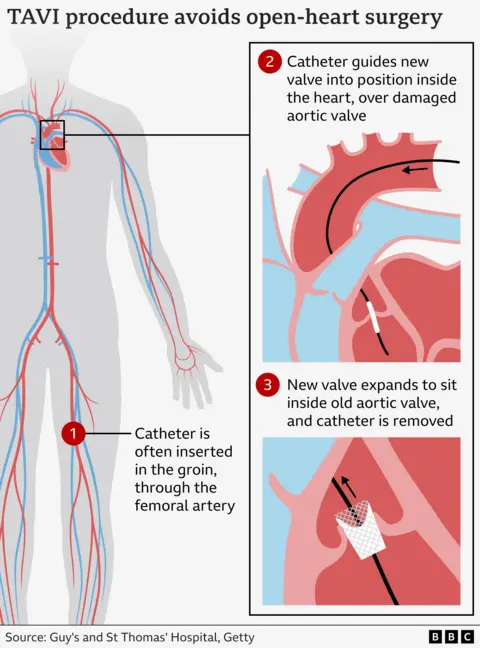

Used instead of open-heart surgery, the TAVI procedure involves inserting a new valve via a catheter through a blood vessel, often in the groin. The catheter guides the new valve to the heart and replaces the damaged one.

The procedure, which typically lasts between one and two hours, is usually carried out under local anaesthetic and is mainly performed on older patients.

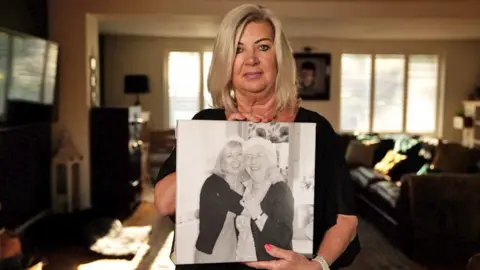

Dorothy Readhead, from Driffield, went to Castle Hill to undergo a TAVI in summer 2020. The 87-year-old, an active member of her local church and a keen gardener, had been suffering bouts of breathlessness which doctors had blamed on a heart condition.

Deemed not suitable for open-heart surgery, Mrs Readhead was keen to take up the option of the less-invasive procedure. “She thought it would give her a (better) quality of life,” says her daughter, Christine Rymer.

But the operation went wrong.

The care Mrs Readhead received formed part of both RCP reviews carried out on behalf of the hospital trust.

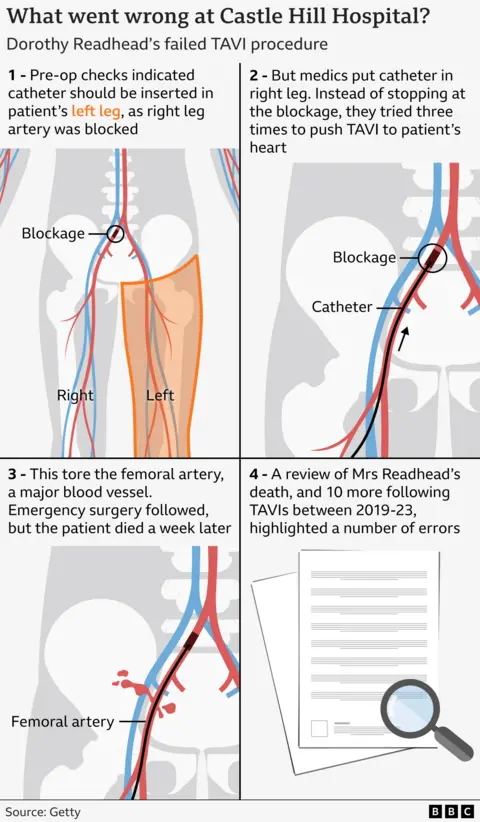

Pre-op checks had indicated Mrs Readhead’s left side was to be used for the TAVI, as her right side had some blockages because of calcified arteries.

The manufacturer of the TAVI device that was to be implanted had also written a technical report clearly stating that access via the patient’s right artery was unsuitable.

On the day of the operation however, the TAVI medics went in through Mrs Readhead’s right leg by mistake. Realising their error, they paused to consider their options but decided to continue – despite the procedure being an elective rather than an emergency operation.

They attempted to deploy the TAVI three times.

The repeated efforts resulted in a significant tear in Mrs Readhead’s femoral artery, a major blood vessel. By now, she had been on the surgical table for six hours, lost five litres of blood, and had been awake throughout.

Mrs Readhead’s care was “graded poor” by the RCP in its 2021 report. It concluded this because of the use of an “inappropriate access site” during a procedure, stating this “unfortunately resulted in an avoidable vascular complication”.

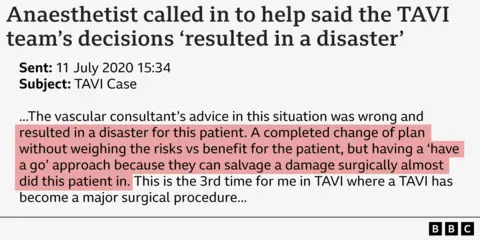

The TAVI team’s decisions “resulted in a disaster for this patient”, an anaesthetist called in to rescue the situation wrote two days after the operation in an email – seen by the BBC.

He described it as “a change of plan without weighing the risks vs benefit for the patient, but having a ‘have a go’ approach”.

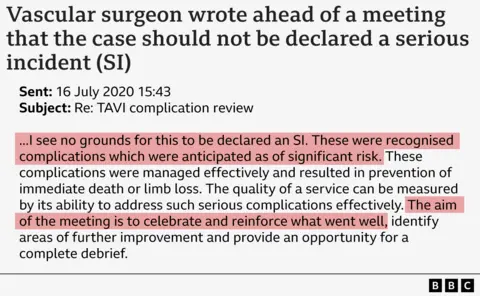

Dr Thanjavur Bragadeesh, then-clinical director of the cardiac unit, suggested the case should be declared a serious incident (SI) when he was made aware of it a few days later. This would mean a full investigation by the hospital.

But this suggestion was initially rejected by the vascular surgeon who had been part of the TAVI team.

“These were recognised complications which were anticipated as of significant risk… The aim of the (forthcoming) meeting is to celebrate and reinforce what went well,” he wrote in an email.

The head of the TAVI team, agreed, replying it was “an unfortunate but well recognised complication”.

The hospital did, however, investigate Mrs Readhead’s case as a serious incident. While it noted that her death, a week after the operation, provided areas for learning, “these would not have prevented the incident from occurring”. It concluded the team had “worked collaboratively and well together”.

This conclusion was shared with Mrs Readhead’s family, with no mention of the TAVI manufacturer’s warning or the failure to deploy the device on three attempts.

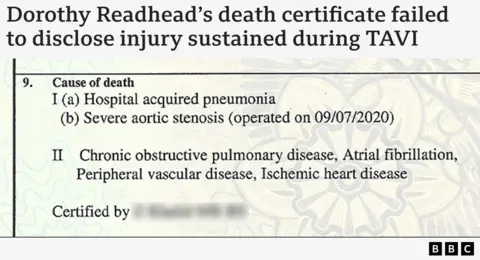

Mrs Readhead’s death certificate also makes no mention of the procedure.

Her cause of death is listed as “hospital-acquired pneumonia and severe aortic stenosis” – the condition the hospital had been attempting to treat.

However, the second RCP review in 2024 strongly disagreed with the death certificate wording.

“The vascular injury during the TAVI procedure should have been detailed, as this led to the patient’s death,” it says.

Mrs Readhead’s daughter says she had no idea what her mother had endured until the BBC showed her the documentation.

“None of that was told to us. None of it,” says Christine Rymer. “It just feels as if mum was a guinea pig, which is not nice to think about.”

The 2024 review looked at the deaths of 11 patients in total – seven women and four men who all had TAVI procedures, including Mrs Readhead. Ten deaths occurred between October 2019 and March 2022 – the other happened in May 2023.

The review’s findings included:

- “Poor clinical decision-making” at every stage of the treatment of a male patient, aged 73 – including incorrect positioning of the TAVI valve

- The same patient’s final death certificate failing to contain an “an accurate description” of what happened. He was issued with two certificates – the first one mentioning a “failed TAVI” was withdrawn, while a second one weeks later stated he died from pneumonia and didn’t mention the TAVI

- Criticism of death certificates issued to two other patients, both women who died within six weeks of each other, saying crucial details were missing, making them inaccurate

- No mitigation for a female patient, aged 84, who had an “elevated risk” – which led to a complication “that might have been avoided under more experienced operators”

The BBC has also seen the 2021 letter from the “very concerned” cardiac consultants to the hospital’s chief executive, Chris Long, and chief medical officer, Dr Purva Makani.

Highlighting one death that year, the consultants said they had been “alarmed to read” that the coroner had not been informed of a serious complication during the operation, with the cause of death recorded as a heart attack.

Dr Bragadeesh, who was one of the signatories, says he believes the TAVI service at Castle Hill should have been suspended at that time because the mortality rate was so high compared to most other UK hospitals.

Former fisherman Brian Hunter, from Grimsby, was another of the 11 patients who died. He had faith in the NHS, say his family, although rarely visited a doctor.

He lived by the maxim that “a hot curry or a paracetamol” would cure all ailments – and “if that didn’t work you, you just got on with it,” according to his daughter, Tracy Fisher.

His diagnosis of a heart problem therefore, at the age of 83, shocked his four daughters. But they and Brian were reassured a TAVI procedure would soon allow him to resume his gardening and cooking his Sunday roasts.

However, there was “a lack of urgency” to treat him, according to the 2024 RCP review – and by the time he underwent the operation, in October 2021, he was “a high-risk case… with an increased risk of complication and little margin for error”.

The TAVI team had made technical errors, concluded the review, failing to properly deploy the device which then wrongly allowed blood to leak back into the heart.

Mr Hunter didn’t survive the operation – the Royal College graded his care as “very poor”. His daughters – just like Dorothy Readhead’s family – had no idea what had happened during his operation until we showed them the report.

“We were led to believe that dad had a heart attack on the table and unfortunately passed away,” said Mrs Fisher. “To find out three years down the line that what your father actually passed from wasn’t the truth is torturous.

“I feel angry as well, and so does the rest of the family, that (the hospital) just outrageously lied. At no point do any of us find it acceptable. It’s just not.”

After raising concerns about Mrs Readhead’s case in 2020, Dr Bragadeesh was asked to step down from his role as clinical director of Castle Hill Hospital’s cardiology department as part of a wider leadership reorganisation.

When the rationale for the reorganisation was challenged, the trust asked the RCP to conduct its 2021 review, including assessing whether the decision to change the management team and his role was correct.

There were poor working relationships within the cardiology department, found the RCP at that time, with reviewers adding that they “positively acknowledge the decision to step down the cardiology leadership roles”.

Dr Bragadeesh continued to work at Castle Hill but took the trust to an employment tribunal.

In December 2023, the tribunal dismissed three of his 29 complaints and said of the remaining 26 that they were out of time, concluding he should have brought his case earlier.

He now works at a different NHS trust. He says the failures identified in the 2024 Royal College of Physicians review “show I was right to raise concerns about the TAVI procedure”.

The Humber Health Care Partnership – which runs Castle Hill through Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust (HUTH) – said in a statement: “We understand families may have questions and we are happy to answer those directly.”

It said that following a 2021 review, the RCP concluded the TAVI service was essential for the region, but said the design of the service should be reviewed and invested in.

“The report offered a number of actions for improvement and we have delivered against all of those since it was shared with us,” it said.

It said its services retained the confidence of the healthcare inspector, the Care Quality Commission.

The trust added that three separate external reviews had been undertaken “and shown that mortality rates associated with TAVI are similar to national mortality rates over a four-year period”.

The mortality data it shared with the BBC indicates that the unit remains above the UK national average.

Additional reporting by Tara Mewawalla