This young disabled man dreamed of getting a job – the system had other ideas

BBC

BBC“I want to contribute to society. I dream of living with friends in supported living, not far from St James’s Park, and getting a job.

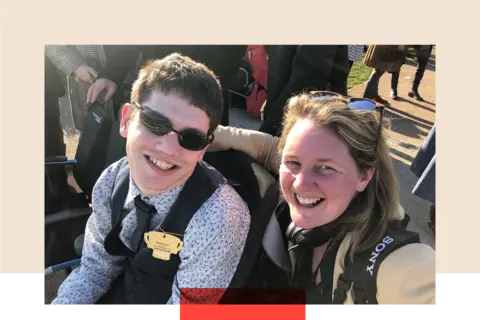

This was the message from Elliot Caswell, a 19-year-old Newcastle United fan who has quadriplegic cerebral palsy, when I first met him on a flight in 2019.

I could see her determination as she was assisted by the aisle staff – to fly independently for the first time, so she could go skiing.

It was clear that she had cerebral palsy, something that was important to me because my younger sister, who also had cerebral palsy, had passed away at age 23 just a few months earlier. Elliot and I started chatting, and it turned out he and my sister played together when we were kids.

Being a camerawoman and journalist, I asked if I could follow him as he transitioned into adulthood. Navigating the system proved more challenging than Elliott expected.

a life of my own

Elliot has cerebral palsy and just wants to contribute to society. He wants to be with friends, with the support he needs, and to have a job that pays. But are the systems in place to ensure that Elliott’s dreams can be realized?

Watch on BBC iPlayer

Last year, the then Conservative government published proposals which it said would help more disabled people into work. Former Work and Pensions Secretary Mel Stride said at the time: “We know many people would like to get back into work with the right support.”

Campaigners welcomed the focus on supporting more disabled people in the workforce, but there were concerns about strengthening benefit restrictions, with the Institute for Employment Studies think tank challenging the “divisive rhetoric” around the back to work plan .

When I met Elliott he was one of those people who were eager to enter the workforce after completing their education.

But now he has lost hope. So what went wrong?

Education

On leaving school, Elliot was initially offered a place at a college near home, which his parents described as “completely inappropriate”. It was for three days a week and designed for people with autism, but Elliot is not autistic. So they took their local authority, North Tyneside Council, to a tribunal.

For people with disabilities, access to quality education can make a huge difference.

A study by the Education Policy Institute think tank found that there were “deeply concerning” discrepancies in how children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) are supported compared to their non-disabled peers. are three times less likely to have any qualifications. and face disproportionate barriers to accessing higher education.

Good practice may include tailored supports, assistive technology such as screen readers and adapted keyboards, and physically accessible spaces – but many institutions lack appropriate accessibility, and some people with disabilities report that teachers do not receive adequate training. While the costs associated with obtaining housing can be prohibitive.

finding paid work

After happily graduating from National Star in 2022, Elliott moved to Project Choice, a specialist college that provides tailored educational support. He was excited about his future and hoped to gain an NHS apprenticeship.

Elliott didn’t want to “sit at home on the benefits system” and wanted to get out, work and meet people, he said.

Work and Pensions Secretary Liz Kendall recently confirmed the Government’s commitments to its manifesto Back to Work plan, which includes plans to support more disabled people and those with health conditions to enter and stay in work .

He said the government would devolve more power into local areas to provide more “joint” support.

When Elliot looks for an apprenticeship, he suffers a series of failures that symbolize the breakdown of the system under stress. Due to the Covid outbreak and lack of suitable work places, he could not get the required work experience.

His mother Chris said that many of the placements were not satisfactory because either he could not fit his wheelchair in them, or they did not have accessible toilets. North Tyneside Council says it is not aware of any placement being offered that was unsuitable for wheelchair access. A spokesperson for the authority says it has “worked hard to secure opportunities that best suit Elliot’s needs”.

But Elliot did not get his long-awaited apprenticeship. He was very disappointed.

Elliott is not alone in his struggle to find employment. People with disabilities are almost twice as likely to be unemployed as non-disabled people.

Recent ONS employment figures for disabled people show that the disability employment gap – the difference in the employment rates of disabled people and non-disabled people – is at the same level as it was before Covid.

Although the proportion of people with disabilities who are in employment varies significantly depending on the type of disability, the gap was 27.9 percentage points in the last quarter of 2023.

Since Elliot has not been able to get an apprenticeship, his local authority has extended his time in education.

Hopefully this will help them develop workplace skills and gain more experience. He is pleased, as he is eager to do some kind of job, even if it is voluntary.

North Tyneside Council contacted 25 organizations to help them secure a position, but admitted there were shortcomings in finding meaningful and accessible placements. Elliott has now joined the Council on a voluntary appointment in a customer-facing role.

Accommodation

Finding work can be hard enough when you have your living arrangements organized, but it’s even harder when it’s not. And for young disabled adults like Elliot, who can live independently with the right supports, it can take a long time to obtain suitable housing.

Elliot had to wait for two years.

I looked at some of the recommended flats with Elliot and his mother and saw how unsuitable they were for his needs. Appliances such as fridges and washing machines were not accessible and bathrooms did not meet her mobility needs.

During those two years he was offered six places to live, but each time his family or occupational health team found him unsuitable. The council says it has worked with the family to find the right home for Elliot, at his pace and in line with his wishes and ambitions.

Chris described the process as “highly stressful” and said it contributed to his recent heart attack.

It was clear that the need was far greater than suitable places to live.

The lack of accessible or adapted homes for people with disabilities is a problem – 91% of homes do not provide even the minimum level of accessibility.

Adopting a home that isn’t accessible doesn’t come cheap. The average award of a government-funded Disability Facilities Grant is now around £9,000.

It was also not possible for Elliot to hang out with mates as each person is managed as an individual case by the local authority – meaning it would be difficult to secure a flatshare with friends. Even flats with more suitable amenities have to be compromised.

While he waited for housing and work opportunities, Elliot moved back from college to his parents’ house, and I watched him lose confidence and independence. I noticed that his mom often spoke up for him during our catch-up video calls and Elliot admitted that he felt “forgotten.”

Recently he was able to live in a shared house, not with friends his age but with a non-verbal man 40 years his senior. The living arrangements are working well.

Elliot’s residence is near his beloved St. James’s Park, and he is very happy to finally leave the house. Their new venue now houses his football memorabilia, and the facilities and care packages they have are excellent.

Elliot has also received vital one-to-one support to enable him to socialize with people of a similar age.

A spokesperson for the authority says, “Finding suitable accommodation for any of our residents, particularly those with a disability or long-term condition, is a priority for North Tyneside Council.”

But according to National Star College CEO Lynette Barrett, many young people like Elliot become young adults with “no clear transition plan” for where they will live.

He said many people end up in inappropriate living situations where their needs are not met and in the worst case, some’s health declines and even they die.

“We should not be in a situation where they have to fight so hard for the basic things in life that they need to be able to live a fulfilling life.”

Eleanor Binks, director of adult services at North Tyneside Council, says the authority works with its partners to provide housing and opportunities for residents with complex needs like Elliot: “We recognize that we don’t always get this right , but we listen and will care about each individual and continue to work to adjust their care to meet their needs.”

She adds: “There are challenges in the health and social care sector that can only be addressed by well-resourced changes to the system.”

calls for change

Elliot is thrilled to finally have his own place, but he has found the uncertainty difficult.

She has held three voluntary appointments, including one at a museum. He worked at the reception there and is currently doing the same work for the council.

But Elliot says he has now lost hope of getting a paying job.

A House of Lords report published today says young disabled people face persistent barriers to employment, even as they look to progress in their careers. It says that many people are ignored and told that ‘people like them’ can never succeed.

It says the government needs to focus on providing support early on, ensuring young disabled people can find work and stay in it after leaving education, and supporting employers to create inclusive workplaces. Must work with.

The stabbing death of a schoolboy tells us about the dangers of Chinese nationalism

How have social media algorithms changed the way we interact?

Dream victories and nightmares for Labour: Starmer’s 100 days in power

What struck me during filming was how the current system is making Elliot and his family feel. It lacks the respect for his quality of life that he should have as he transitions from a child to an adult.

His twin brother, Lewis, said that Elliot has worked very hard with the help of his parents, but “shouldn’t have to try so hard” to get the future he wants. Lewis also has cerebral palsy but it only affects him on one side, meaning he is able to walk without assistance, hold salaried employment and live with friends.

Elliot’s enduring determination is an inspiration. But after years of trying to secure his independence, he concludes: “You can’t rely on the system to help you.”

Additional reporting by Polly March

Top photo credit: Getty Images

bbc indepth The best analysis and expertise from our top journalists has a new home on the website and app. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and in-depth reporting on the biggest issues to help you understand a complex world. And we’ll also feature thought-provoking content from BBC Sounds and iPlayer. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking the button below.