How worried should we be about Mpox?

Reuters

ReutersThe rapid spread of ampox – formerly known as monkeypox – in Africa has been declared a global emergency.

The new form of the virus is a matter of concern, but many unanswered questions still remain.

Is it more contagious? We don’t know. How deadly is it? We don’t have the data. Is this going to be a pandemic?

“We have to avoid the trap of thinking it’s going to be COVID again and we’ll have to lockdown — or it’ll be like COVID in 2022,” says Dr. Jake Dunning, an MPox scientist and doctor who treats MPox patients in the UK.

To assess the threat despite the uncertainty, we must first understand that this is not one ampox outbreak, but three.

All these events are happening at the same time, but their impact on different groups of people and their behavior is also different.

They are labeled by their “clade” — basically which branch of the ampoxvirus family tree they come from.

- Clade 1a is causing most infections in the west and north of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). This outbreak has been going on for more than a decade. It spreads mainly through eating infected wild animals known as bushmeat. People who are sick can spread the virus to others they come into close contact with and children have been particularly affected.

- Clade 1B is a new branch of the ampox family and is causing outbreaks in the eastern part of the DRC and neighbouring countries. It is spreading along trucking routes, where drivers have heterosexual sex with exploited sex workers, with infected people also spreading it to children through close contact.

- Clade 2 is the ampox outbreak that spread worldwide in 2022 and again had a strong association with sex, this time mainly affecting gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men communities (in the UK 98.6% were men) and their close contacts have also been infected. This outbreak is not over yet.

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibraryTruck drivers and sex workers

Clade 1B is one of the main reasons the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency of international concern. This strain has spread to countries previously unaffected by ampox – Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda.

It was first reported this year, but genetic analysis has shown it originated in September 2023 in the gold mining town of Kamituga in the DRC’s South Kivu province.

“The mining town has a sex industry and because of the heavy movement of people it has spread rapidly to bordering countries,” Leandre Murhula Masirika, research coordinator for the Department of Health, told me from South Kivu.

He said paying for sex is the main way the virus spreads, but it also spreads from parent to child or between children and is linked to abortion.

The outbreak of this new Clade 1B branch appears clearly different from that of Clade 1A.

“It is really different because the rash is more severe, the disease seems to last longer, but it is most likely caused by sexual transmission and person-to-person contact and we have not seen any association with bushmeat,” Professor Trudy Lang, from the University of Oxford, told me on Radio 4’s Inside Health programme.

An important question is why? The answer is either growth or opportunity.

The new strain appears genetically different, but there is no solid evidence yet that these mutations have made the virus more infectious.

Exposure to sex workers, who have close contact with other people, will further accelerate the outbreak.

“The fact that transmission through sexual networks occurs more rapidly does not mean that the virus itself is more contagious,” Dr. Rosamund Lewis saysThe World Health Organization’s Ampox lead gave this information.

This virus is not a sexually transmitted infection. However, it spreads through close physical contact and sex obviously involves close contact.

Reuters

ReutersLike the early days of HIV

An ampox outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo this year has killed more than 500 people. The threat to the country and its neighbors is clear.

“We have not been able to control the virus in South Kivu,” says Leandre Murhula Masirika.

“We need large-scale interventions to control and contain this outbreak.”

Professor Lang, who is working with teams in the DRC, makes the comparison to the early days of HIV. When I questioned him on this he said it was a phrase that was “not used very often and certainly not lightly”.

She says: “This combination of young exploited sex workers, families, truck drivers and obviously the children around all of that are the most vulnerable victims of this outbreak and this was also the case in the early days of HIV, where it really spread because of trucking routes.”

A global threat?

Mpox is not expected to be a COVID-level event. It has been almost a year since the new strain emerged in September 2023.

In the UK and other countries, the most likely scenario is that someone will return with the virus and become sick.

This has happened several times before with Ampox in the UK and Canada. Cases of ampox continue to be reported Linked to the 2022 Clade 2 outbreak.

These imported cases may be the end of it or there may be limited spread within households through close physical contact. Sweden had the first clade 1b case outside Africa, with no further spread reported.

Even more worrying would be if a young infected child takes it to nursery or pre-school, where he or she plays with other children and causes an outbreak there.

This is the limit of what is considered possible in Britain.

“No, I don’t think it’s going to be a big deal,” Dr. Jake Dunning said.

“I’m a little bit upset and irritated that people are only focusing on what happened in 2022 and thinking that’s going to be the case.”

Reuters

ReutersThe answer would be to find people who have come in contact with an infectious person and vaccinate them, rather than running a mass vaccination programme.

Imported cases like this would be easier to track in the UK than in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where conflict and humanitarian challenges have grown.

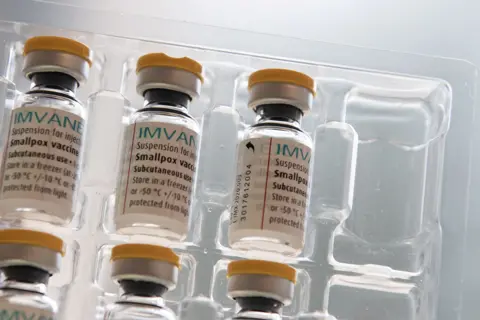

There are still no ampox-specific vaccines available, but smallpox vaccines work against the disease.

Both smallpox and monkeypox viruses are orthopox viruses and immunity to one confers protection against the other.

The end of the smallpox vaccination campaign – following the eradication of the disease in 1979 – is one of the reasons we are now seeing m-pox on the rise.

People who were vaccinated against smallpox as children have older immune systems now, but they should still have some protection.

As will vaccinated men during the 2022 outbreak, although the Clade 1 outbreak is not disproportionately affecting gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men.

The people who need vaccines most in Africa are those at the epicentre of the pandemic.

Dr Dunning said: “We are very poor at sharing tools to prevent ampox, particularly vaccines, and that is inexcusable.

“It’s clear to me that the biggest win for us is controlling these outbreaks at the source.”